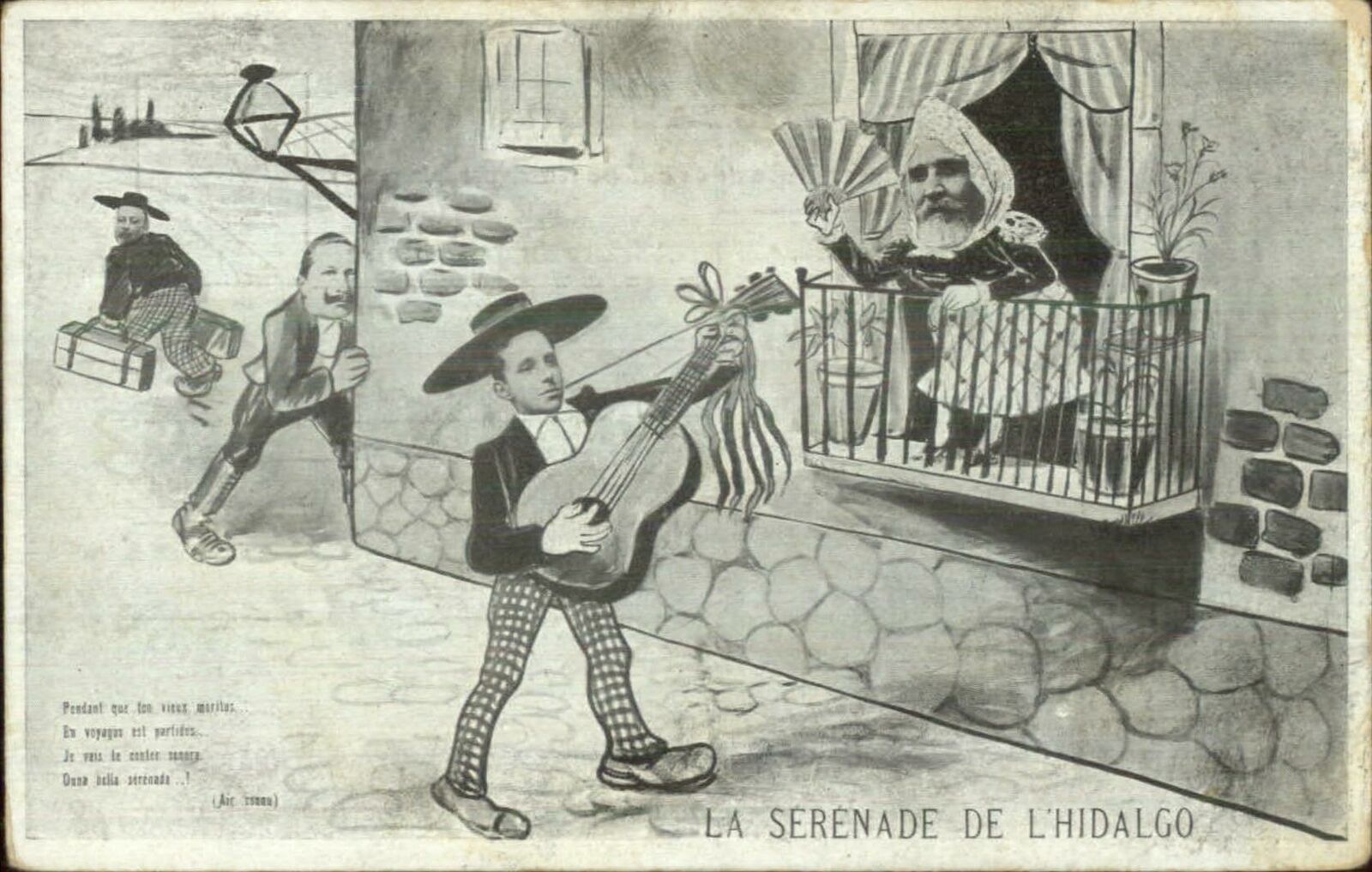

The

Satirical

Serenade:

Opera,

Music

Halls,

and

Mocking

Tradition

Long

before

television

or

internet

skits,

satire

found

a

melodic

home

in

opera

houses

and

music

halls.

These

venues,

brimming

with

song,

dance,

and

theatrical

flair,

played

host

to

comedic

critiques

that

entwined

entertainment

with

social

commentary.

Whether

ridiculing

political

elites

or

skewering

everyday

norms,

the

satirical

serenade

flourished

as

audiences

reveled

in

irreverent

humor

delivered

by

costumed

performers.

Opera

buffa,

the

Italian

comic

opera

tradition,

rose

to

prominence

in

the

18th

century.

Unlike

the

lofty

tragedies

of

earlier

operas,

these

works

embraced

lively

plots

and

down-to-earth

characters.

Composers

like

Mozart

contributed

to

the

genre

with

pieces

such

as

The

Marriage

of

Figaro,

which

gently

mocked

aristocratic

privilege

by

featuring

cunning

servants

outwitting

their

noble

masters.

Set

to

enchanting

music,

the

comedic

punch

hit

softer

yet

lingered.

Viewers

hummed

the

tunes

while

reflecting

on

the

social

hierarchies

the

lyrics

lampooned.

In

19th-century

Europe,

music

halls

and

vaudeville

stages

took

the

baton.

These

rowdy

environments

gathered

working-class

crowds

hungry

for

comedic

relief.

Singers

might

belt

out

a

chorus

that

lampooned

a

local

politician’s

latest

scandal,

or

dancers

could

reenact

a

farcical

version

of

current

events.

The

mixture

of

boozy

patrons

and

spontaneous

performances

fostered

a

carnival-like

atmosphere,

where

jokes

about

authority

felt

almost

liberating.

Audiences

could

snicker

at

the

powerful

in

a

communal,

raucous

setting.

Such

satire

often

hinged

on

caricatures.

Performers

assumed

larger-than-life

personas—whether

as

pompous

generals,

bumbling

bureaucrats,

or

flamboyant

socialites.

Through

exaggerated

costumes

and

comedic

songs,

they

made

each

target

simultaneously

ridiculous

and

memorable.

The

comedic

style

was

direct

and

accessible,

ensuring

that

even

those

with

minimal

education

could

grasp

the

punchlines.

After

all,

a

buffoonish

king

struggling

to

keep

his

trousers

up

needed

little

explanation.

Yet,

censorship

loomed.

Governments

monitored

theaters,

wary

that

comedic

routines

might

spark

dissent.

Some

composers

and

librettists

resorted

to

abstract

or

historical

settings,

effectively

critiquing

contemporary

rulers

under

the

guise

of

mocking

distant

monarchs.

Others

took

advantage

of

comedic

stereotypes

to

obscure

references

to

real

individuals.

The

result

was

a

playful

cat-and-mouse

game,

with

satirists

pushing

boundaries

and

authorities

occasionally

stepping

in

to

ban

shows

deemed

too

provocative.

Meanwhile,

certain

artists

cultivated

a

“safe”

level

of

mockery.

Rather

than

challenge

the

entire

political

system,

they

poked

fun

at

universal

human

foibles—vanity,

greed,

or

lust.

This

approach

resonated

with

middle-class

audiences

who

appreciated

moral

lessons

wrapped

in

humor.

In

many

ways,

these

comedic

performances

acted

as

a

pressure

valve,

allowing

social

tensions

to

vent

through

laughter

rather

than

rebellion.

By

the

early

20th

century,

music

halls

gave

way

to

music-based

revues

and

variety

shows

on

radio

and

eventually

television.

But

the

lineage

remained

clear.

These

formats

continued

the

age-old

tradition

of

pairing

catchy

tunes

with

witty

banter

to

highlight

collective

absurdities.

Whether

lampooning

industrialization

or

modernization,

the

satirical

serenade

endured,

proving

that

society’s

hunger

for

comedic

commentary

never

dies.

Today,

musicals

on

Broadway

or

the

West

End

sometimes

channel

the

same

spirit,

weaving

comedic

critique

into

song

and

dance.

Even

comedic

operas

still

appear,

reminding

modern

audiences

that

the

power

of

harmony

and

melody

can

sharpen

satire’s

edge.

The

satirical

serenade

endures

as

a

testament

to

performance

art’s

capacity

to

amuse

while

quietly,

or

brazenly,

nudging

us

toward

introspection

about

the

folly

of

those

in

power—and

in

ourselves.

Originally

posted

2011-04-20

09:07:30.

Go to Source

Author: Ingrid Gustafsson